I first saw Ayad Sinawi’s paintings a few years ago during a visit to his studio in Long Island City. Working in a few different modes of representation – at times cinematic, sometimes schematic and abstract – they evoke deep feelings of longing and a desire to connect with the viewer. I recently visited his studio again and I left feeling as though he had turned it up a notch in terms of pictorial ambition. The following short interview talks about, among other things, some of the overriding themes that pervade his work and his sources of inspiration.

Art Blah Blog: You’re currently (mostly) using three modes of representation – the large, for lack of a better phrase, “cinemascope” pictorial paintings, the cloud grids, and the map-like overlays that are schematic and more akin to abstraction. Before we go into any of these in any detail, do you encounter some conflict in the studio as to what you’re going to work on?

Ayad Sinawi: Firstly, thank you Andrew for giving me this opportunity to discuss my work.

As to your question, yes there is usually a little conflict every time I step into the studio, not because I’m conflicted about which painting (or type of work) needs my attention at that particular moment, but instead has something to do with the amount of time I can dedicate that day to my studio practice in general.

Working thematically and in series have always been a process I felt most comfortable within. I have iconoclastic tendencies and have resisted establishing a recognizable style from early on in my work.

Because I feel that the different themes in my paintings are component parts of the same puzzle of a unified vision, bringing the different elements together tends to define in my mind a co-dependency toward meaning. I feel liberated by not being consigned to a style. I owe a lot of that to my temperament as a painter, but also to being a student of the eighties at a time when postmodern skepticism was pushing painting, and art in general, to redefine the image in terms of pluralistic constructs.

ABB: In all of your work, I found it interesting that your color palette was very consistent between these modes, but was also aware of the different feelings that each evoked. I assume that one mode is scratching an itch that the others don’t. In our recent studio visit, you alluded to the fact that all of your work speaks about similar issues. I’m assuming that you’re tackling the same subject matter from different, if complementary, sides. Do you ever have visitors who can’t connect it all?

AS: My color palette has always been limited to values that evoke earthiness, decay, and nostalgia. I never forgot a statement a professor of mine made long ago about the use of oil paints, how painting with oils is like painting with the earth of the planet, how it invoked life. I liked his metaphor, and in many ways, it helped me solve the problem of color early on. It’s not a case of indifference to color as much as it is an ambivalence. I hope that the “emotionality” of color can therefore strike a chord of narrative meaning instead of being purely a synaptic response to what color ought to trigger in us emotionally.

I alluded in your first question to my different modes of working as complementary collaborations toward an attempt at unified meaning. I try not to tempt a thesis-like reading of why that is, but hope that I can invoke these relationships in terms of aesthetic responses that may hopefully illuminate a sense of connection in the viewer.

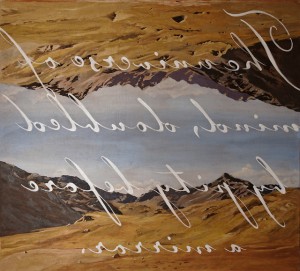

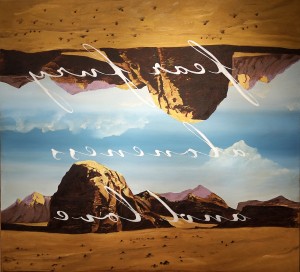

ABB: I see a relationship of paintings like The Universe Of Mind, Doubled By Pity Before A Mirror to surrealist (Dali and Magritte) and some 80’s painting (like that of David Salle or Julian Schnabel, though better painted) in your use of reversed lettering and its doubled landscape. I usually think of these kinds of paintings as emotionally remote, but your works are instead confessional and heartfelt. Of course, the reversed lettering functions as a way of keeping the content at arm’s length, but not unreachable and, to my mind, imbues that confessional aspect with a sense of fragility. The emotions in this piece and Fear Fury Aloneness and Love feel big and cinematic. The lettering, in it’s flowing, arabic-like script, augments this sort of romantic worldview. You’ve mentioned that these landscapes are composites of various sources, creating a kind of ideal place or dreamscape. Would you talk about the process in creating these paintings? Related, do you sometimes feel that your work is exposing? I ask because many artists whom I know seem intent on keeping any emotional content out of their work altogether, or at least keeping it very peripheral.

AS: I wanted to use language in these paintings as a way to fold back one layer of interpretation back onto the image. I was intrigued by the idea of Plato’s cave as an allegory of our understanding of reality which seems even more timely today, and so I wanted to find some kind of a visual solution that was not didactic but personal. The mirroring afforded my a way to express that notion. By doubling the image on itself I was hoping to both suggest the allegorical cave, and establish a visual motif that suggests an opening/exit onto a different reality from the one projected behind us. There is a whole bunch of different interplays going on here: the scale of the painting, which you aptly suggested as cinematic, the relationship of the image to the body of the viewer, the interpretation of the allegory and our metaphorical departure away from the cave’s wall toward a new understanding of reality.

The reversed text adds another layer of meaning of course, because once again, its reversal is in itself a play on the idea of walking away and being able to read it in the rear view mirror after the fact.

I have to say that my intention was not necessarily to keep viewers at arm’s length. The reversed text was a way to merge narrative to image as an invocation of personal memory. Confessional or not, the viewer’s deciphering of what the reversed text said was my way of hopefully involving them in this merger.

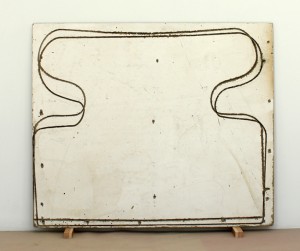

ABB: The cloud grid pieces like The Color of the Sky Divided are fascinating to me, insofar as each rectangle is a cloud “world” that I could get involved with. At the same time, there is a tension in wanting to look at the adjacent rectangle, and so on. During our recent studio visit, I commented that the clouds have associations of freedom and dreaminess, but that by having these all gridded, they could also be read in terms of suffocation or imprisonment. What do you think of this interpretation? Would you also talk about where this cloud imagery comes from and what experiences inform these images?

AS: The grid structure was the only way for me to move ahead with making these paintings. I don’t think I would have been interested in a painting depicting clouds without defining the image via plurality and repetition. You hit it on the head about the duality I was after in making these images. The temporal non containment of how a cloud actually behaves, versus how I force the images to co-exist inside a rigid grid structure, both window-like and container. These clouds are imagined scapes made from observations but are never fixed to an actual image. I observe and I photograph the sky constantly, but rely solely on memory and gesture to “sculpt” the cloudscapes into place.

I do however disagree with the notion of imprisonment and suffocation. Locking the image within a series of gridded paintings are instead a way of observing things that are temporal and unfixed otherwise. Clouds are just another aspect of experience and memory as invoked by its own self-referential ubiquity.

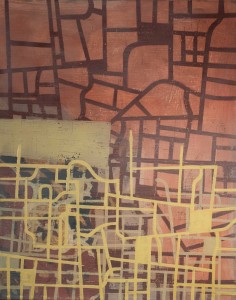

ABB: Well, it’s sort of becoming an Art Blah Blog tradition that I interpret work differently than what the artist intended! That said, the map paintings like Magical Thinking seem more hard-headed to me. With their overlays, they bring up associations of, say, the way a city might evolve from one century to the next, of streets and people discarded and displaced. I also thought about the experience of someone’s lifetime – moving from one city to another.

AS: Here is another literary source that although I read many years ago, was a foundation for how I wanted to explore the grid paintings. That book was Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, and the notion of the imaginable in literature stuck with me as I tried to find a way to put an almost literal and diagrammatic element to play alongside grids and lines that has had a long history within modernism’s fascination with geometric abstraction.

Obviously, the links I make to city grids are self-evident, and there has been for me a long period of fascination with cities as evolutionary organisms. The stacking, layering and the interweaving of grids are metaphors for added experience that are both personal and corporeal. I was interested in manifesting those ideas by making the actual doing of the paintings the subject of their meaning without stuffing the work with opaque theoretical foundations. If I dare to say it, the meaning is in the action of doing.

ABB: On a related note, you spoke about about how your work was sort of a outgrowth of the classic immigrant experience, a result of a peripatetic early life. Especially in the large cinematic pieces, it occurred to me that you were creating paintings of places where you could feel a sense of home or belonging. At the same time, there seems to be an effort to talk about a sense of disorientation as well, a tension between that ideal and its attainment.

AS: Painting is a way of fixing location and defining for me what belonging is. I always saw the act of painting as a political act in as much as it declared a free will to explore and process ideas of “home” and my personal freedoms to engage with the world around me. As a child growing up in the Middle East, that would have been unthinkable had I stayed. However I am not making political work at all. I don’t even consider my work as diaristic in narrow specific terms. I aim for beauty and materiality, I take pleasure in throwing contrasting motifs against each other and seeing what happens (or doesn’t happen). I like to doubt myself because that is how I arrive at answers. It frees me to work poetically and rigorously, but without the deep filter of self-editing.

ABB: Have you seen any shows of late that impressed you?

AS: One exhibition that stayed with me was Kour Pour’s painstakingly detailed large scale paintings of Persian and near Asian carpets at Untitled. They are labor intensive recreations of photographic sources from various European and American auction catalogs. They not only act as simulacrum of the real thing, but bring to focus our relationship to marketable commodity versus functional and humanistic utility in beautifully direct ways. They also spoke to me about how direct experience can sometimes lead to a reinterpretation of the familiar. In Mr Pour’s case, he grew up surrounded by Persian carpets as his father was a carpet dealer in England, so the images are rife with personal meaning as well as the social and cultural dimensions associated with such an economic pursuit.

ABB: You’ll be showing three paintings at Jeffrey Leder Gallery* as a part of the group show, International Painting NYC III (opening Sunday February 23, 2014). Any other shows on the horizon?

AS: I am exploring different avenues to exhibiting my work abroad, but I’m currently more content to make the work and explore scale and gesture within the confines of a studio practice unencumbered by expectations and deadlines.

*Jeffrey Leder Gallery is located at 2137 45th Road in Long Island City, NY; Phone: 917 767 1734; http://www.jeffreyledergallery.com/

To see more of Ayad Sinawi’s work, go to: http://ayadsinawi.com/

All images copyright© Ayad Sinawi