I first became acquainted with Jeff Feld’s work during a Bushwick open studios when he opened his house/art space in Ridgewood to visitors. Most prominently displayed were his cardboard sculptures which I immediately took a liking to. After speaking with him for awhile, he generously shared a number of other projects – drawings, paintings, collage, and other sculptures that often used materials in an inventive and unfussy way that evoked a sincerity and formal accomplishment. I confess that I found it difficult to wrap up the raft of associations in a tidy package – which I believe to be the point. To quote from his artist’s statement, Feld’s work “…attends to and embraces the vicissitudes, banalities and failures of the day to day.” . This short interview doesn’t pretend to discuss Feld’s work in a comprehensively detailed way, but instead tries to provide a general overview of his thinking and process.

Art Blah Blog: You seem to get a satisfaction out of using fairly humble found materials for your work – foam rubber, wallboard, cardboard, office envelopes and the like, and repurposing them as artwork of various kinds to express an uncomplicated but pleasing abstract sensibility, as well as a kind of connection to the larger world. Can you take me through your process a bit? Does it involve trolling dumpsters, building sites or Home Depot with specific thoughts as to how these materials might be used?

Jeff Feld: Hi Andrew, thanks for inviting me to speak with you on your art blog. It’s always fun running into you out in the trenches. I’ve never trolled a dumpster for art. That being said, I like the whole idea of dumpsters as objects in general because, like this interview, they provide a context for collision and exchange of meanings. Dumpsters have a lot of material but I rely on local hardware stores and art supply stores, mostly, and buy what I need in a very prosaic, law-abiding way. Given the nature of my work there is sometimes a question as to where my hand interceded versus what existed before and I like this unintended consequence.

There is an emphasis on material in my work. It’s not so much that I get satisfaction out of these materials, but rather that I’m interested in materials and use them to express or reveal a particular feeling and meaning. I’ve always used materials in this way. Certain bodies of work required a high degree of skill. For example, the hand sculpted and cast earthenware used in “Service Station,” or my work “Pelican” in which I meticulously recreated a Rauschenberg performance. My holy water works use a sacred substance to recreate images of the Madonna and child on large pieces of industrial sponge. Godliness is next to cleanliness.

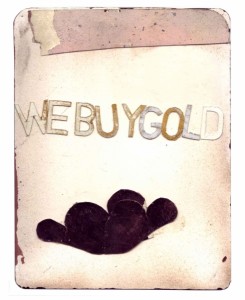

I use materials that I feel are consistent with the type of space – emotional, physical and literal – that I want to create. Pleasing, uncomplicated, dumpster diving – I wouldn’t associate any of those terms with my work, or with my central interests. For the last couple of years I have been thinking and making work about the banality of everyday life and the failures we encounter daily. We find ourselves confronted by dysfunction and surrounded by materials that are ubiquitous, cheap, and transitory. My use of cardboard, concrete, spray paint, and so on, are very much consistent with the day–to-day experience I share with millions of others. These materials do provide a connection to the larger world but, more importantly, they provide an entry point for the viewer to experience something that is larger than what I present. These associations allow for discourse that expands outside of the gallery and over time.

ABB: My take is that the materials keep throwing the real world back at the viewer, so that we become involved in a chain of associations outside of the usual “art world” concerns. There seems to be a sort of tragicomic content in your work, specifically in works like A failure of the day to day and Stop and frisk that have an implied sort of narrative. Would you expand on this?

JF: I’m not really interested in the usual art world concerns in that I really don’t know what they are anymore. I would acknowledge that in the past I’ve probably pushed my work in an art world direction that seemed to be somewhat cogent to me but I think for me it is better to invest my energy into Jeff Feld concerns. From my viewpoint it seems that as visual artists we operate under the increasingly large shadow of language and money and in many ways these pervert the essence of how my work functions. How often have you had a curator come into your studio, spend a few moments and then ask you to tell them what the work means? These are people who are supposed to know something about attending to and discerning meaning! I give the viewer an in, and perhaps a context clue, then the rest is up to you. I’m not saying that I don’t like talking about the work, but viewing art is not a facile enterprise. While I have produced works – most recently a project I did with the Queens Museum of Art entitled Queens takes Kings – that clearly rely on language and interpretative materials, on the whole I prefer producing works that are less dependent on a fixed narrative that gives them meaning. I want my work to exist and have meaning in and also outside the white cube. When I choose a title for a work my aim is simply to set a mood, perhaps give a little push, but not in a singularly prescribed direction.

Tragicomic is a good word to describe my current work. The confounded condition of the things I make resonates with what I observe in the world. I wouldn’t say that the work is narrative based, but rather that the work is socially based, it speaks, to social concerns, the problems of all manner of relationships in everyday life, the constant falling short of expectation, and the shifting meaning of the objects we encounter.

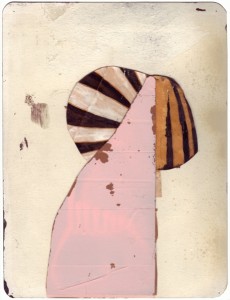

ABB: On a related note, your work seems “friendly” to me, but not “cute”. Do you find that your use of found materials keeps the aesthetic a bit more grounded, a bit grittier? In particular, the small collages that you make have a sweetness to them, without being sappy. Do you sometimes step over the line and destroy a piece if it goes over a particular line? Related to that, are there any particular reasons that would make you destroy a piece (besides accidentally dropping it)? How much revising do you typically need to do?

JF: The only found materials in my work are used inter-office mail envelopes that I take from my day job. I guess, technically, they could be classified as stolen objects. I’m phasing them out but I like these envelopes because they provide a record of interaction among people and as such serve as indexical devices. My drawings provide an index of interactions between myself, materials, and space. My drawings have no corners, I trim the corners into a rounded edge. This decisive act creates a defined space, and alludes to an object of containment. I only destroy work if it becomes exhausted of meaning (for me) and I can’t remember the last time that happened. I’ve had a dog destroy my work with great gusto and pleasure as well as a critic or two but that’s it. I change works, though; everything before me in the studio is malleable in some way and I think the ability to push something in a different direction rapidly without fear is essential to my studio practice. I wouldn’t come to blows about adjectives, but my drawings don’t evoke friendly and sweet for me. I think their scale and materiality make them human; like us mortals, the drawings are subject to duress but are resolved, after struggle, and become true to themselves.

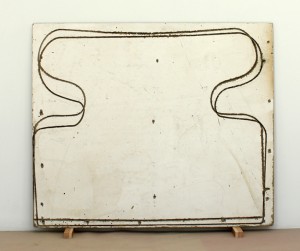

ABB: When I visited your space, the series of painted cardboard sculptures, The intention is pure and so on… looked to me as though they were made out of wood. I was surprised to find out that they were cardboard. Most of your stuff is very up front about what it is made of. The disguised aspect of these specific pieces seemed part of a larger strategy, but I’m not sure if I completely understood the intent, though I found the disguise itself intriguing and I appreciated the work formally. Was there an element of enjoyment in putting one over on the viewer, and/or was this disguise part of a larger theme for these pieces?

JF: To talk about a work in only formal terms is a canard. I don’t think we can ever separate form from content. The works that you describe are very interesting to me in the context of my broader work as I view them as transitional works, moving through a slow and labored, “smart” approach through to my current work, which is immediate and decidedly dumb. The works that compose “The intention is pure and so on….” hint at modernist forms yet have no specific reference point – instead they seem castoffs from the larger modernist project, long forgotten yet somehow evocative. These hollow works are fake in the sense that their histories are created in the studio and the use of cardboard belies this falseness. I’m not trying to put one over on the viewer but instead bring an idea, that the modernist project is empty and over, into three-dimensional form. The title speaks to earnest ambition yet it negates itself.

ABB: Just a couple of obligatory questions to end the interview. Were there any shows that impressed you lately?

JF: There is so much out there to see that I can hardly keep up. Out my way in Ridgewood/Bushwick, I really appreciated Meg Lipke’s work at Parallel, Meg Hitchcock at Studio 10 and Dave Hardy over at Regina Rex – I’m still thinking about Dave’s show and it’s been a few months, looking forward to seeing how his work progresses.

Two stand out shows for me were -Stay in Love, organized by Chris Sharp and Tony Feher at Sikkema Jenkins. Stay in Love took place in two galleries, Laurel Gitlen and Lisa Cooley. The show resonated with me in every way and included a super great B Wurtz work as well. Tony Feher at Sikkema and Jenkins was gorgeous – I’ve never given Tony’s work a whole lot of thought but I thought this show was beautiful and evocative, I’m thinking about him in a whole new way. These powerful works were articulated using an economy of means that I truly admire.

ABB: Do you have any shows coming up soon?

JF: Maybe, sort of, kind of – and then again perhaps not – I’ll share some details when I can.

Interviewer’s note: the title of this interview courtesy of Jeff Feld.

All images copyright© Jeff Feld.